Last time I asked the question: But is any of this significant?

I think it is. The two forms of wire weaving are distinctly different in form. The Nahlbinding form uses a distinctive looping pattern, known in fiber circles as the Coptic stitch. In addition, the Nahlbinding form, like Nahlbinding that is done with yarn, uses relatively short pieces of wire, usually 12 to 18 inches long, that are joined together to form a woven chain or some other form. The knit form uses the same pattern as the knit stitch in Knitting. The knit form also uses a continuous piece of wire. The length of this wire is limited only by the ability of the maker to create it.

So now we have a problem. The original form of Trichinopoly, is the knit form. But historically it has not been sorted correctly from the Nahlbinding form. The teacher in my Gulf War class chose to call the Nahlbinding form “Baltic Wire Weaving”. The problem with that is that it certainly did not originate there. Several years ago I found a piece of it in the touring exhibit of the female pharaoh, Hapshetsut, which puts the date back to 1508–1458 BC, and Egypt is no where near the Baltic.

I don’t really have a solution for the naming problem, but I do have another VERY important point to make. When I began in the SCA many years ago I was told that knitting was not done pre-1600. Then latter I was told it was brought to Spain by the Arabs and was used there by about 1200. Then I ran across the fact that during the reign of Henry VIII a law was enacted requiring all men to wear a knit cap on Sunday, and another stating that women must wear white knit caps unless their husband was of considerable social standing, and only the nobility could wear knit goods that were produced outside of the realm. And then about four or five years ago the Museum of London digitized, and made available, an extensive collection of knit coifs, flat caps and other items that are pre-1600.

But what does that have to do with Trichinopoly. Simple. The original identified form of this wire weaving, the Trewhiddle Hoard, is believed to have deposited about 868 AD in the Cornwall area of England. And there appear to be other pieces in Scotland and Ireland. That puts the structure of knitting in the British Isles before 868 AD, considerably older that the 1500’s.

Now we have the opportunity for more research. In Scandinavia we find Nahlbinding used for both fiber and wire. In Egypt we see both knitting and Nahlbinding techniques used in fiber. The Victoria and Albert has a Nahlbinding pair of socks, and I have personally seen the same technique used in jewelry. Can we locate the knit structure in Egypt in wire jewelry? And in the British Isles we find the knit structure at least as early as 868 AD in metal. Can we push it back farther in metal? And can we find it in fiber? Fiber is much more easily destroyed by time and the environment than most metal, but bogs can preserve animal fibers, like wool. The time has come to actively revisit old finds, in both metal and fiber, with a thorough understanding of knit and Nahlbinding structures. The time has come to make sure that researchers are well versed in the nuances of wire weaving structures.

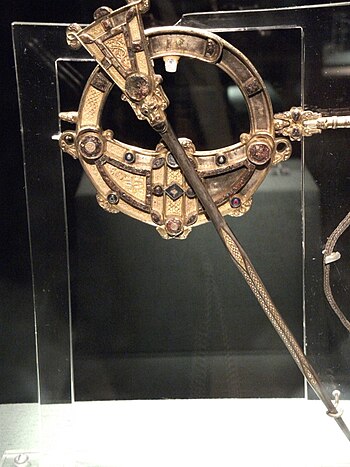

Dated approximately 872-5, based on coins in the hoard. Found at Trewhiddle, Cornwall, England 10: Curved ornamental mounts, function unknown 11: Scourge (whip) made of tube-knitted wire, with plaits and knots, with a glass bead attachment 13: Decorated pin with hollow head 15: Flattened ornamental strip of unknown function 16: Decorated strap end 17: Bronze buckle, with the tongue missing 18: Plain cast strap ends and belt slides 19: Coins and coin fragments (Photo credit: Wikipedia)