I am a class junky.

I just finished taking six days of classes and watching at least an additional dozen demonstrations before and after class. My classmates included people from the United States, Canada, Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala. I am officially tired and suffering from information overload, but I am also very happy and looking forward to actually using all of the new skills that I have learned.

Where did I go? The Rio Grande Winter Workshop in Albuquerque, NM. Why there? I have been to Rio events before and they bring together some of the finest jewelry and metal working teachers in the world, all in one location, for six jam-packed days. Vendors like Fordham, Swanstrom Tools, Fretz Hammers, and Bonny Doon Press, just to name a few, send representatives and do demos, and in some cases actual classes. In addition to their Winter Workshop they also do individual classes during the rest of the year on a variety of jewelry topics.

But what if you can’t travel to a major international class event? What can you do closer to home?

Regional schools greatly reduce the need to travel large distances.

In North Carolina the Penland School of Crafts is a major learning location for all sorts of arts and crafts. Most regions of the US have locations like this. Haystack Mountain School of Crafts on Deer Isle, Maine is open year round, but holds most of its classes during the summer.

There are also plenty of schools that specialize in a particular area of study. For example, in the Boston area, MetalWerx runs jewelry classes all year, plus special workshops in the summer.

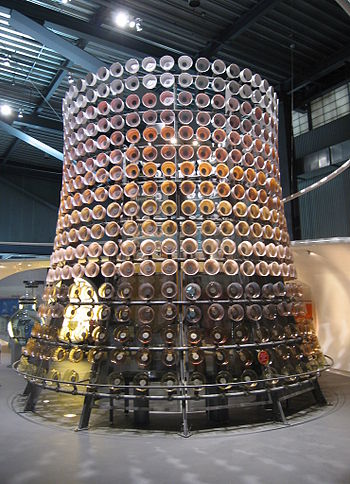

In Corning, New York, the Corning Museum of Glass runs a huge number of glass working classes – everything from making glass beads to glass sculpture and glass blowing.

Beyond the private schools, community colleges often provide a very affordable and local alternative for learning. When I lived in California I used to drive down to Monterey Peninsula College once a week for an all day jewelry class. They have extensive continuing education classes in addition to their regular curriculum, and occasional weekend workshops.

Adult Education programs often have a wide selection of classes available, usually at very affordable prices. Local craft stores, both privately owned, and big box, often teach a wide variety of classes that relate to the products that they sell.

But what do you do if you don’t live close to the classes that you want to take, or the classes do not fit your schedule? I will discuss that next time!