Last time I mentioned the fact that a lot of pre-1600 items are actually quite a bit smaller than we might modernly assume. In addition I mentioned the easy manufacturing techniques involved in lead and tin items.

Bronze requires dramatically more heat – nearly four times the heat! Temperatures near 2000° F require a furnace, with some sort of blower system, like a bellows. Bronze items would therefore have been a more specialized and expensive production. Not as elite as silver or gold, but not the bottom rung of lead and tin either. And even more important, bronze is much stronger than tin or lead.

Getting back to tiny things, let’s talk a little more about tiny brooches. Tiny brooches can’t be used on thick fabrics. This does NOT mean that they can only be used on linen, cotton, or other plant fiber fabrics. It just means that the fabric needs to be relatively thin.

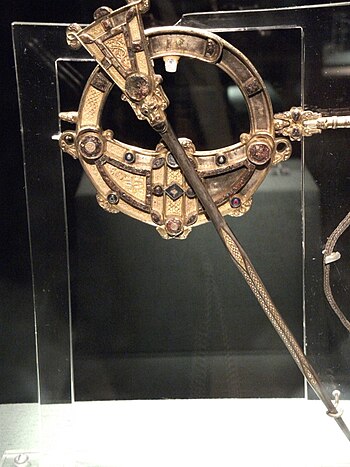

Brooches like the little one that I bought have a big advantage over penannular brooches. A penannular brooch, if tugged and shaken enough can eventually open. But an annular brooch has to break, bend a lot, or have the fabric that it is attached to tear in order to let go. This gives it a couple of big advantages over the other forms of simple closures that were available pre-1600. It won’t open and it can lay super flat.

The brooch on the left is an annular brooch and the one on the right is a penannular brooch, with a dime for scale (18mm). I chose a heart shaped annular brooch because I wanted to make a point about annular brooches. They must form a closed ring, but that ring can be just about any shape.

The brooch on the left is an annular brooch and the one on the right is a penannular brooch, with a dime for scale (18mm). I chose a heart shaped annular brooch because I wanted to make a point about annular brooches. They must form a closed ring, but that ring can be just about any shape.

What forms of closures were available pre-1600? Laces or ties, hooks, hooks and eyes, buttons and toggles, penannular brooches, annular brooches, fibulas, dress pins, and other miscellaneous brooches. We already discussed penannular and annular brooches, so let’s look at the other options – remember we are looking at tiny things here, preferably things under half an inch, because that was the size of my little brooch. And there must have been a reason for that size, right?

Laces and ties. Easy to make, inexpensive and widely used. They can be made by the average person with commonly available supplies. They can be made to lie extremely flat, but they can break or untie, and it is very difficult to make them really tiny and still have sufficient structural integrity.

Hooks, and hooks and eyes. Exactly what is the difference? Modernly hooks and eyes are small metal sewing accessories that are available at any sewing supply store. Pre-1600 folks did have small hooks and eyes that were made out of metal wire, and they were definitely used extensively in the 1500’s, but there were also many other types of hooks used, and even some large cast hooks and eyes. Earlier cultures, like the Celts and Anglo Saxons sometimes used what I call “hooks and eyes on steroids” – sets where the individual pieces are each an inch or more long.

This picture shows a modern selection of hooks and eyes in various sizes on the right (the numbers are the sizes) and a 1500’s collection of hooks and eyes, from the Netherlands on the left. The size 3 modern hook is about 7/16th inch tall (12 mm).

This picture shows a modern selection of hooks and eyes in various sizes on the right (the numbers are the sizes) and a 1500’s collection of hooks and eyes, from the Netherlands on the left. The size 3 modern hook is about 7/16th inch tall (12 mm).

So, if size is an issue the large hooks are out. The tiny hooks and eyes can lay fairly flat, and they meet the size criteria, but unlike many of their modern versions they did not have a little “bump” on the inside of the hook that make the hook and eye set “lock”. This means that the older hook and eyes would have to rely on tension pulling on them and keeping them in place. Without the tension, they open.

Next time: Hooks – Sharp and Blunt, and Buttons and Toggles