Making paper in Europe used rags as a raw material. Rag pickers bought and sold used clothing and other fabric until it was no longer suitable for anything but making paper.

Paper pulp was made using rags. The mills would cut rags into small pieces, at the same time removing any buttons, hard seams, badly stained pieces etc… These little pieces would then be piled in a dark corner, soaked with water and allowed to rett (rot) for a couple of weeks. Fungus growing on them was a sign of good retting.

The next step was to take these retted rags and put them into a stamper. This was a series of very large wooden hammers powered by a water mill. It pounded the rags in water to pulverize the rags into individual fibers. The process essentially “unmade” fabric by separating the fibers from the spun yarn and thread.

The pulp was then added to a large vat and diluted so that the final concentration was probably about 95 percent water and 5 percent fiber. The vatman would then use a large frame with a large number of parallel wires strung across it, lower it into the pulp and pull out a screen load of what will become paper. The fiber in the pulp lays flat upon the screen creating a thin layer of pulp.

After pulling the screen the vatman shook it to consolidate the fibers in the pulp and passed the frame to a coucher who then flipped the frame onto a layer of damp wool or felt. The coucher then placed another piece of felt on top of the very fragile sheet and passed the frame back to the vatman who repeated the process. This continued until a stack of alternating pulp and felts as large as could fit into the press was made. This stack is called a post.

Paper in the post was extremely fragile until it was pressed. An apprentice would move the post to the press and apply pressure to the stack using a long wooden handle in a paper press. Once the excess water was pressed out of the post, the individual sheets of paper could be hung to dry on ropes, hung in groups on ropes, or placed on drying cloths.

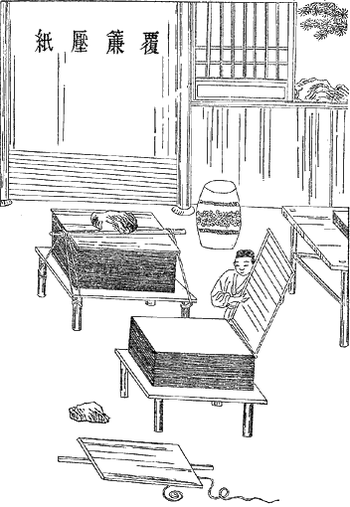

16th Century Vatman image courtesy of British Association of Paper Historians (ca. 1588). The stamper or hammer mill used to pulp rags can be seen in the upper left of the image. The paper press is located in the upper right of the image. Note the holes in the wooden screw through which a wooden handle was placed to press the wet paper. Other images show this handle to be about 3-4 feet long enabling substantial pressure to be applied to the paper. The vatman can be seen lifting a mould from the pulp vat. The mould includes a deckle frame which is set on top of the mould to consolidate the paper edge. In the lower left an apprentice is carrying a pressed stack of paper to be dried. If you look out the windows you can see the water wheels that are used to drive the automated processes, like the stampers.

Next Time: Making Paper at Home