The name ‘paper’ comes from the original source of paper, the papyrus plant. Renaissance European paper is made of pulped cellulose fibers such as cotton and flax. According to tradition (but not documentable), paper was first made in China about AD 105 by Ts’ai Lun.

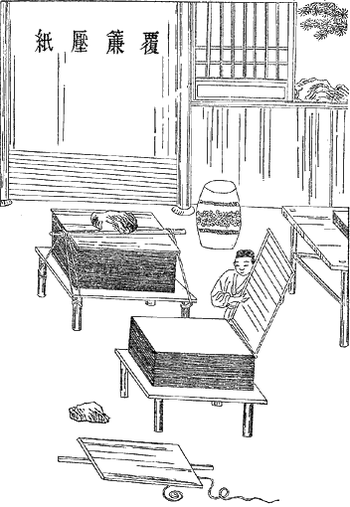

An image, describing five major steps in ancient Chinese papermaking process. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Paper making is generally recognized as diffusing throughout Europe from the Arabic countries. Arabs in turn acquired the knowledge of paper making in the area of Samarkan located in modern day Uzbekistan. They set up paper mills in Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo, and later in Morocco, Spain and Sicily. Although the Samarkan region grew cotton and used it for making paper, the Arabs generally lacked fresh fibres. Consequently the Arabian paper making tradition was based almost entirely on rags. The breaker mills employed in the Arabic paper making process produced an inferior pulp. But, by using this method, with screens made of reeds, thin sheets of paper could be made with a good quality. These sheets were coated with starch paste as a sizing. This gave Arabian paper its good writing properties and fine appearance.

One of the better documented paper making endeavors in Europe was that of the Nuremberg councilor Ulmann Stromer (Stromeir). In the late 14th century Stromer employed skilled workers from Italy to transform the ‘Gleismühle’ (flour mill ) by the gates of his home town into a paper mill. The dates noted in his diary, 24 June 1390 (start of work on the waterwheel) and 7 and 11 August 1390 (oaths sworn by his Nuremberg foremen), are the first documented records of papermaking in Germany. A facsimile of these diary pages is on display at the Deutsches Museum of Science and Technology in Munich.

The wording of Stromer’s diary entries reinforce the impression that papermaking was a largely unknown and secret art, consistent with practices of secrecy by the Guild system in Europe. Stromer had to convince the immigrant Italians to teach him the necessary papermaking secrets. In addition, he had to overcome many technical difficulties. Stromer’s mill – illustrated in the world chronicle of Hartmann Schedel in 1493 – was initially designed with two waterwheels, 18 stamping hammers (i.e. six holes) and 12 workers using one or two vats.

Italian papermakers had improved the Arabic methods by developing:

- the use of water power

- the stamping mill (derived from the stampers and milling machines used in textile handicrafts)

- the mould made of wire mesh (as a result of progress in wire production), which triggered the introduction of couching on felt

- the paper press (screw press) with slides for feeding in the material

- drying the sheets on ropes

- dip sizing

Handmade paper in the western tradition requires the work of three professionals. First the Vat man scoops the pulp from the vat containing a mixture of water and pulp and forms a piece of paper on the mould. Next the Coucher transfers the wet sheet of pulp to a damp felt to be pressed and give the paper a particular surface. Finally, the Layer removes the wet sheets from the felts and stacks them for further pressing and drawing. The layer is also responsible for removing defective sheets.

Watermarks are created by sewing a formed wire into the mesh of the paper mould, creating a slightly thinner layer that reveals the shape of the watermark when held up to the light. Watermarks were used to identify the paper maker and were first in the forms of circles, crosses and stars and other religious symbols relevant in the 13th century AD.

Next Time – Papermaking: The Process